It's not

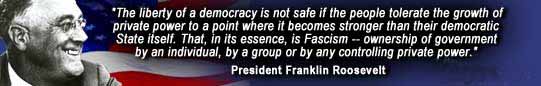

about being liberal or conservative anymore y'all. That is a hype offered by the fascist whores who want to confuse the people with lies while they turn this country into an aristocratic police state. Some people will say anything to attain power and money. There is no such thing as the Liberal Media, but the Corporate media is very real.

Check out my old Voice of the People page.

|

|

|

Loyalty without truth is a trail to tyranny. |

|---|

|

George Washington |

POSTS |

|---|

GOTO THE NEXT 10 COLUMNS

|